The Commodore’s great-granddaughter keeps the bay close to her heart.

“When I was younger, I was shy about having this heritage,” says Mary Munroe Seabrook. “My high school teacher would single me out in class. Later, I really came to embrace it.”

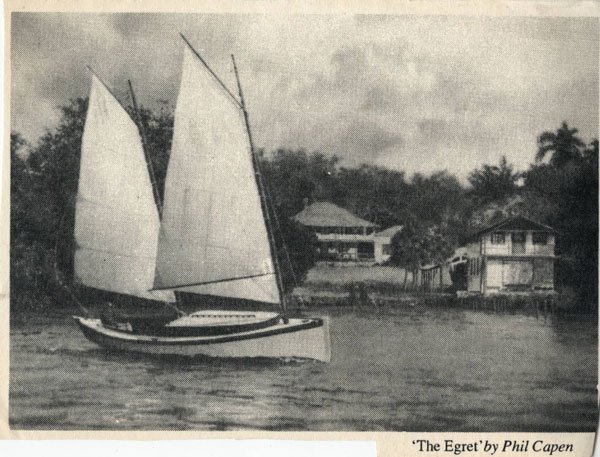

Surely, the heritage may have weighed awkwardly on the teenager whose great-grandfather was none other than Commodore Ralph Munroe, the 19th century pioneer from New York, renown designer of sailing yachts, early photographer, and naturalist also known as the Father of Coconut Grove. Yet four generations later, Munroe Seabrook lives what her predecessor surely dreamed — a way of life intimately connected to the bayshore that preserves “the beauties and possibilities of this country,” as the Commodore wrote in 1877.

And she lives it just a stone’s throw away from The Barnacle, Commodore Munroe’s unique bayshore home, which became a historic state park in 1973. Munroe Seabrook served on its board in the early 2000s.

“I think my family assumed that us kids would be ambassadors,” she says. “I was raised on a steady diet of civic engagement and volunteerism. And I really stepped up in my adulthood.”

Memories abound for Munroe Seabrook.

“My grandma had a room stuffed floor to ceiling with historical photos, naval and architectural drawings,” she recalls. “After she died, my dad and uncle went through it all. It was like opening a treasure chest — some of it going back 200 years.”

Later, Munroe Seabrook would attend the opening ceremony for the Ralph M. Munroe Family Papers collection at the University of Miami Richter Library.

Munroe Seabrook’s own two daughters, now in their teens, took field trips to their great-great-grandfather’s homestead as students of neighboring Carrollton School. “One year, I took them instead when they were in the Brownie troops,” she remembers. “They really felt a special sense of history there. I got my dad to come. I think they felt really proud. I like to think I’m grooming them to take over the role of legacy and Miami history.”

Following historic footsteps

Part of the Commodore’s legacy is literally under Munroe Seabrook’s feet and was hiding in plain sight for many years.

The Commodore Trail, a centuries-old Tequesta footpath along the coastal ridge and hammock forests between the Rickenbacker Causeway and Cocoplum Circle, became a rock road in the late 19th century. In 1969, Miami-Dade named the five-mile stretch, which in some sections is barely distinguishable, after pioneer Munroe.

“I’ve been riding that trail my whole life,” she recalls. “Two summers I worked at the Museum of Science day camp and I biked from Old Cutler. Since my kids were three, I’d walk or bike them to Carrollton School. Until the new pedestrian bridge at Cocoplum Circle was built, I didn’t know this trail had a name.”

In 2019, Munroe Seabrook co-founded the non-profit Friends of the Commodore Trail with carbon-free mobility activist Hank Sanchez-Resnick to advocate for the maintenance, safety and beauty of the historic pathway. Like her co-founder, Munroe Seabrook is also passionate about bicycling and walking as viable — and healthy — forms of transit and recreation.

“We knew it had been severely neglected,” she says. “Part of the problem is that it runs through the city, sometimes in people’s yards. The brick sidewalk in downtown Coconut Grove is also part of it — right there with café tables and valet stands.”

Child of the bay

Munroe Seabrook also inherited sea legs from the Commodore, who founded the Biscayne Bay Yacht Club in 1887. “I grew up with this,” she says. “We were always at the club on weekends, and sailed the Comanche, a 40 ft. cutter rig designed by my grandfather for Jack Price, an Olympian sailor. My maternal grandparents brought it from Price when I was born. It’s still in the same slip!”

Munroe Seabrook’s parents knew each other from a lifetime of sailing on the bay. She met her husband at Stiltsville, the rickety collection of wooden houses built on the bay. The couple has also taken their daughters out bay cruising on the Comanche.

The bay is in her blood and bones, and surely the Commodore would be proud.

“I’m proud that I can handle a boat. Not many women can do that,” she says. “I wasn’t discriminated against as a girl to learn sailing. We used to joke about the Jimmy Buffet song: ‘I was the daughter of the son of a son of a sailor.’”

Another watercraft that keeps her deeply connected to the bay is a paddle board. “Our street ends up on the bay,” she says. “That’s what I really love to do.”

On any given day, she might be paddle boarding with a friend, or Molly, a miniature Golden Doodle who loves the water. She might find herself gazing at the sunrise on the very same shores where the Commodore dreamed about the future of a tiny hamlet and its lush coastline. And he probably would have loved his great-granddaughter’s quiet independence.

“I see so much marine life,” she says. “Manatees, spotted eagle rays, even crocodiles. I observe the birds and clouds. I love being on the water on my own terms.”

What is your passion?

“My family.”

What do you love most about the Grove?

“I love its walkability and bikeability. I would never drive. Even if I go out at night. My kids do, too. They walk or bike to school. I’ll even ride in a light rain.”

What makes the heart of the Grove beat?

“The dedicated people who work through organizations to make the Grove a better place.”

What is your superpower?

“Tenacity. When I get an idea in my head that I want to do something, I make it happen.”